Arsenal Still Searching For the Perfect Balance

Arsene Wenger was talking about a striker who he signed in his second season in charge at AS Monaco, the Argentine Ramon Diaz. In training, he would say Diaz was so focused on his finishing that

“every time he missed a chance, he went absolutely mad. I said to him ‘calm down’ He said to me: ‘Boss, I played 8 years in Italy; I had one, maximum two chances per game. I knew if I missed one, my game was over.’ That’s a little bit [similar] to the Premier League. You do not get 10 chances. You do not get five. You get one or two and you have to put them away.”

It was this anecdote, with a caveat of sorts, which Wenger chose to repeat before Arsenal’s 1-1 draw against Leicester City, on the eve of the summer transfer window, seemingly throwing the gauntlet to his strikers to be more clinical or be replaced. Arsenal’s riposte was a positive one, shooting 24 times at goal; though at the end of the game Wenger bemoaned the lack of clear-cut chances created. Alexis Sanchez opened the scoring with a near open-goal after Yaya Sanogo had fluffed his lines, but Arsenal were pegged back three minutes later when Leicester equalised and were then able to sit back and comfortably able to see the game out for a draw. The next day, Wenger reacted and splashed out £16m on Danny Welbeck.

In a nutshell, this anecdote also sums up Arsenal’s season, though it’s at the other end of the pitch where it is most relevant. That’s not to say Arsenal have solved their (relatively normal by most standards) goalscoring troubles; Welbeck has slotted straight into the starting line-up but his two league goals is not enough of a return for the promise he’s shown. His hat-trick against Galatasaray was a tantalising demonstration of what he can deliver: a high-class display of controlled aggression mixed with clinical finishing, but on the main, he’s been a little too nice, Will Smith nice.

By and large, however, Arsenal have been bailed out by Alexis Sanchez, whose impact – eight goals and two assists in the league – would have been more salivating if not for the frustrating way Arsenal continuously shot themselves in the foot.

Arsenal’s last fixture was a perfect case in example. The Gunners, having taken the lead with a fine counter-attacking move, finished of course by Alexis, should have then found the restraint within themselves to sit back and soak up the impending pressure that was to come from Swansea. Instead, on a dank, wet evening in Wales, they flooded bodies forward in an attempt to get another goal and were punished, as four minutes later, and two goals worse off, the scoreline was reversed. It was a similar story against Anderlecht four days earlier when Alexis contributed with a superb volleyed goal to help Arsenal to a three-goal lead before they threw it all away for a draw.

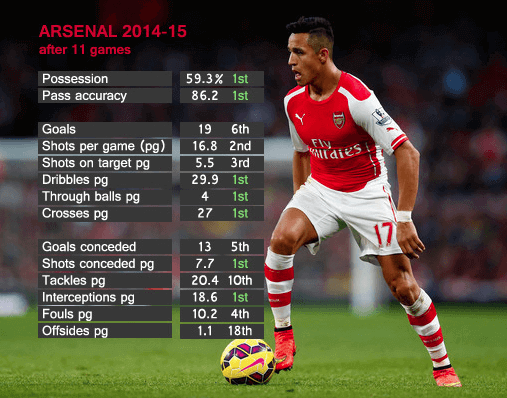

Contriving to drop points has been Arsenal’s main problem this season. In a broader sense, it has been Arsenal’s problem for a long time, but last season, however, The Gunners, on the main, managed to reverse that trend by controlling moments better. That is, they ensured that they were a goal up, or at 0-0, for as much as the match as possible, before exploiting their opponents’ tired legs. Arsenal’s failure to do that this season explains why their underlying numbers – their possession per game, shots, dribbles, interceptions etc. – have been very good, yet their position in the league is average by comparison.

The problem, as Michael Caley explains for the Washington Post, is that Arsenal “struggle in the clutch” – that is they tend to fall short in the crucial moments that come between winning and losing, and when the pressure is up. To underline the point, Arsenal have scored first only six times this season, and have gone on to win three of those matches (Burnley 3-0, Aston Villa 3-0 and Sunderland 2-0). Two out of the six matches they have drawn (Leicester 1-1, Hull 2-2) and lost one (Swansea 2-1). On the one hand, however, they have shown some resolve by rescuing a point or winning four out of the five times they have fallen behind by conceding first (Man City, Everton 2-2, Spurs 1-1, Crystal Palace 2-1). The issue is, though, that Arsenal have spent more time losing (244 minutes) than winning (175 minutes), and even when they are winning, contrive to conceded goals very quickly.

As Caley explains, shooting conversion increases or decreases depending on what the game state is. He says, “in general, when a soccer team is losing by a goal, it will convert its shots at a lower rate than when it is winning by the same score. Teams tend to outperform their expected goals by several percentage points when winning and under-perform when losing. This is most likely an effect of defensive pressure. Winning teams will sit back and keep more men behind the ball, while losing teams will push forward looking for an equaliser. And indeed Arsenal has done much more of their attacking in less favourable game states compared to most of their competition.”

What makes it worse for Arsenal is that opponents only need to attempt a paltry amount of efforts to score a goal. Currently, Arsenal concedes a goal every 6.4 shots. Wenger pinpoints much of this down to confidence, not focusing enough at key moments or succumbing to complacency when The Gunners do score. Certainly, there is an argument that the defensive efficiency in Arsenal’s game is not there yet. Last season, Arsenal managed this by being pragmatic, by retreating to a low defensive block and then hitting teams when they showed mental or physical tiredness – usually through the lung-busting runs of Aaron Ramsey.

This season, they have failed to find efficiency because the team still seems to be unsure of what it wants to do at various stages or yet, haven’t acquired the game intelligence to carry it out; whether to press high up or sit back. That can be highlighted by the first goal Arsenal conceded in their 2-2 draw against Hull City.

Here, Jack Wilshere urges Santi Cazorla to press when nobody else is, eventually leaving Mohamed Diame free to pass to. Wilshere had the right of it to some extent, as Hull’s player had picked up the ball with his back to goal – which should have been the trigger to press – but where he was wrong was that the whole Arsenal team showed no indication to squeeze play prior, with Hull completing 3-4 passes in that area with relative comfort anyway.

In more recent games, however, Arsenal have been more exposed on the break. As Wenger says:

“We have put a lot of effort into our work to be more efficient but we give chances away that very few other teams do. At the moment our opponents have made the most of what we have given away.”

The work Arsenal have put in to be more efficient has been two-fold, recurring around how they keep the ball and how they press without it.

Firstly, on their ball work. Wenger says that the team has “progressed since last season in the way we dominate the games and the way we combine,” which may confuse some given Arsenal’s league position, but what people might be missing are the palpable steps Arsenal are taking to improve to their positional play. In that, Wenger is looking to emulate bits of the Germany/Pep Guardiola/Dutch 4-3-3 model where the attacking line in the 4-1-4-1 occupies the length of the pitch, thereby always creating angles and options to pass to. As Leighton Baines says, in an interview for The Guardian when talking about Everton’s philosophy which goes along the same branch, “the really top teams who have mastered this way (Dutch Total Football), are the ones that gets success.”

On the other hand, emphasis on death by possession makes it tougher for Arsenal to defeat teams as often; defences are set thus making it more difficult to get through. It has made Arsenal more sterile in effect, one of the things Wenger has strived to avoid. However, he has probably come round to see it as a necessary evil because sterile domination is not really an aim for possession teams; rather, it’s a by-product of their voraciousness to have the ball. Keeping the ball better also has the added effect of protecting the team from the counter-attack, an increasingly important aspect when planning your team in the modern game and what Jose Mourinho calls the “fourth phase”: attacking, defending, counter-attacking, and then, countering the counter.

Increased work on Arsenal’s positional play has sought to protect Arsenal from the counter, with players looking to take up positions off the ball so that all key areas on the pitch are occupied. That can be highlighted by the relationship on the pitch between Santi Cazorla and Alexis who switch positions depending on whether one goes inside, or the other stays wide. As Wenger explains, Welbeck can also join in to fill the gaps. In the past, perhaps, Wenger would give too much freedom to his creative players to go where they want but by incorporating little chain reactions, gaps can be covered. In recent games, Wenger has tinkered the set-up to give it a 4-4-2 gloss, though as a result, the team’s fluency has suffered, most notably in the 3-3 draw against Anderlecht where the ball was frequently turned over.

It is thought that an effective possession game must be backed up a fully synchronised pressing system and this is where Arsenal have failed. Perhaps, they’re not suited to such a high-intensity game because it requires concentration and awareness from the whole team and indeed, such a thing was even admitted by Mario Zagallo of his side when coach of Brazil in 1970. “We played as a block, compact,” said Zagallo in The Blizzard, Issue Three). “Leaving only Tostao up field. Jairzinho, Pele, Rivelino, all tracked back to join Gerson and Clodoaldo in the midfield. I’m happy to see the team in terms of 4-5-1. We brought our team back behind the line of the ball….Our team was not characterised by strong marking.”

Certainly Arsenal have missed Laurent Koscielny and Mikel Arteta for certain passages of the season, to of their most astute players, yet on the other hand, the best pressing teams in the past have been led by not necessarily the best runners, but the men on the touchline, usually infectious, obsessive types – Arrigo Sacchi, Pep Guardiola, Valeriy Lobanovskyi, Jurgen Klopp, to name a few. That probably hints at psychological effort required to play such a way, and why perhaps more teams don’t do so when logically, they should because modern players are “taller, faster and stronger, and can press right up to the penalty area” says Arrigo Sacchi. But with Pep Guardiola citing motivational reasons for his departure of Barcelona and subsequently, the lack of pressing from his successor, Tata Martino, it suggests it plays a big factor in coaches using it.

In any case, Wenger says, pressing “isn’t about covering distances, it’s about doing it together” and that probably indicates that he is trying to find a balance between pressing up the pitch in certain moments –Wilshere talks about the five second rule that Arsenal are working on implementing when opponents lose the ball – and dropping back into a compact block. It’s an urgent need for Arsenal to learn quickly because there is a feeling that also there is wasted potential in this side; that with the right configuration, there is an exciting blend in this Arsenal team which is waiting to burst to life.